PROGRAM NOTES

VIRTUAL GALA 2020:

A Gift of Music to the Community

Marc-André Hamelin Program Notes

TOCCATA ON “L’HOMME ARMÉ”

by Marc-André Hamelin

Marc-André Hamelin built his Toccata on “L’Homme Armé” on a French melody that dates back to the 1400s.

Hamelin is one of many composers to make use of the tune. Over the centuries, and up to the present day, composers borrowed the melody for dozens of settings of the Latin Mass. Hamelin’s piece presents the complete melody straightforwardly, after a brief introduction, then lets it develop into a free fantasy that ultimately gathers momentum towards an explosive ending.

The work was commissioned for the 2017 Cliburn Competition. Departing from the established tradition that year, the rules stipulated that all 30 contestants were to play it, as opposed to previous years when it had only been required to be performed by semi-finalists.

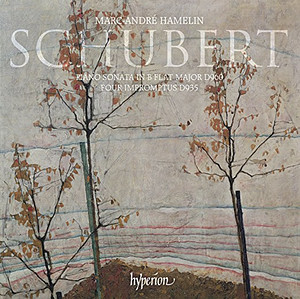

PIANO SONATA IN B-FLAT MAJOR, D.960

Franz Schubert, b. January 31, 1797 (Vienna, Austria)-November 19, 1828 (Vienna, Austria)

‘Who can do anything after Beethoven?’, Schubert asked, rhetorically, in a letter to his friend Josef von Spaun. Beethoven’s mighty example was indeed both an inspiration and a creative obstacle for any composer in Vienna in the 1820s. Yet the great series of instrumental works Schubert produced after the master’s death in March 1827 suggests that the outwardly self-effacing former schoolteacher was eager to establish himself as Beethoven’s successor. This notion rings especially true in the case of the C minor and A major sonatas from the trilogy completed in September 1828, just two months before Schubert’s premature death. In the final piano sonata in B flat major, D960, the Beethovenian influence is at best oblique: a distant recollection of the ‘Archduke’ trio, perhaps, in the serene opening theme; and, in the way the finale approaches B flat via C minor, an echo of Beethoven’s last work, the rondo he wrote to replace the Grosse Fuge in his B flat quartet, Op 130. Yet in spirit the sonata is utterly un-Beethovenian. The profound contemplative ecstasy of the first two movements is, with the G major sonata, D894, and parts of the string quintet, the consummation of a quintessential Schubertian experience first glimpsed in his 1815 setting of Goethe’s ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’, D224.

The B flat sonata has acquired an aura of otherworldliness, as if Schubert were already communicating from beyond the grave. Yet we should be wary of reading it, or its two companions, as a protracted farewell. While Schubert realized that he was unlikely to make old bones, he had no inkling until his final illness that the autumn of 1828 would be his last. There is pathos, and a sense of evanescence, in the sonata but also (in the last two movements) exuberance, humour and a sheer zest for life.

The soft, deep trill on a dissonant G flat that intrudes on the sublime calm of the opening immediately illustrates a crucial difference between Beethoven’s and Schubert’s methods. Where Beethoven would have integrated the trill into the music’s argument, for Schubert it remains something ‘other’: remote, mysterious, an extreme contrast in sonority and register with everything that surrounds it. Only once, in the transition from exposition to development (heard only if the exposition is repeated, as in Marc-André Hamelin’s performance), does the trill erupt in fortissimo violence. But while the trill’s function remains essentially colouristic, like a distant timpani roll, the note G flat does prefigure an important tonal area in the movement: in the leisurely expansion of the main theme that follows the opening statement, and in the F sharp minor theme (F sharp being the enharmonic equivalent of G flat) in the piano’s tenor register that opens the second group.

Like the exposition, the development unfolds with infinite spaciousness. After building to a fortissimo climax—a hint, perhaps, of human anguish in this quietest and most inward of sonata movements—the music hovers hauntingly around D minor, with the opening bars of the main theme, in hushed preparation for the recapitulation. In this context the theme’s momentary appearance, ppp, in a chromatically shadowed B flat has an effect of luminous strangeness, as if the home key is distantly glimpsed through a gauze.

The mood of ethereal tranquillity deepens in the andante sostenuto, a nocturnal barcarolle in C sharp minor. As so often in Schubert’s piano music, the texture of the opening theme suggests string chamber music, above all the famous adagio of the string quintet: it is not hard to imagine a second violin and viola intoning the floating, almost becalmed melody against delicate pizzicatos from the other strings. In the hymnic central episode, set in the warmly contrasting key of A major, the rich texture evokes a trio or quartet of cellos. When the main theme returns it acquires a new murmuring accompanying figure deep in the bass. Before the coda finally resolves into C sharp major, Schubert conjures another of his unearthly visions with a deflection to the fathomlessly remote key of C major.

With its nonchalant shifts of register and delicious harmonic sideslips, the scherzo forms a mercurial interlude between the timeless contemplation of the andante and the more corporeal world of the finale. The minor-keyed trio, with its lumpen off-beat bass, sounds like a skewed, cussed Ländler.

Launched by a held octave G, the rondo finale begins with a Hungarian-tinged dance tune which feints at C minor before resolving into the ‘proper’ key of B flat. In another of Schubert’s gloriously leisurely structures there are several memorable themes, including a gliding cantabile over a rippling accompaniment, and a mock-heroic F minor outburst that dissolves into a skittish dance. Only at the very end is the main theme’s ambiguity resolved, with the octave G slipping to G flat and then to F, before the brilliant, quasi-orchestral send-off. Though he could hardly have known that this would be virtually his last instrumental work, Schubert, like Beethoven in the Op 130 finale, bows out with mingled robustness, lyrical tenderness, and wry, quizzical grace.

Notes by Richard Wigmore © 2018